Sam Fender’s highly-anticipated third album ‘People Watching’ features his signature vivid storytelling and anthemic instrumentation. However, what sets this album apart from his previous works is that it’s his least personal.

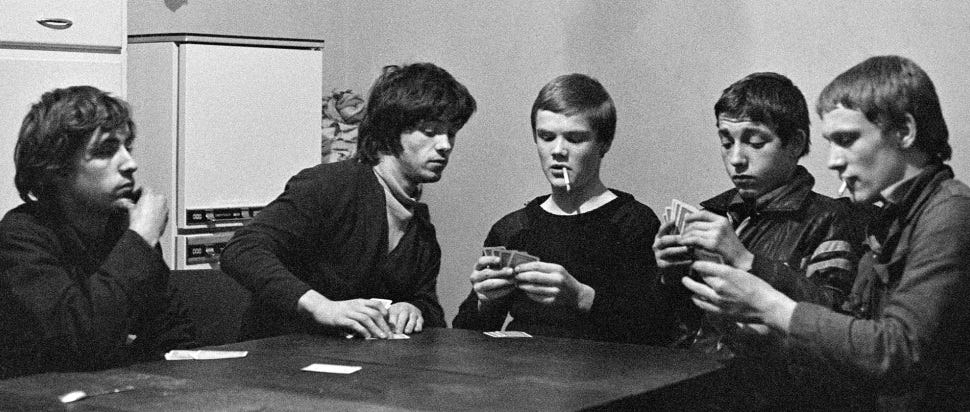

This can be interpreted before you even press play. The artwork is a black-and-white photograph of a group of young men playing cards. It was taken by the late Tish Murtha, a photographer from South Shields whose work documented working class life in North East England.

This is a sharp contrast from the artwork of his previous two albums: ‘Hypersonic Missiles’ (2019) and ‘Seventeen Going Under’ (2021). The former features a high angle medium shot of Fender staring directly into the camera, whilst the latter shows him sitting on a wall outside a house in North Shields, his hometown. Both of these album covers cement Fender as the central figure within his albums; they’re his stories, his opinions, his voice.

However, by substituting himself with the figures in Murtha’s work, Fender positions himself as the people-watcher. He explores the familiar themes of class, substance abuse and death, but with a certain level of detachment that has spawned from his success. He is no longer the people in the photographs; he is now Murtha, pointing the camera and clicking shoot.

Thematically, the idea of Fender as the observer is very strong. Whether you’ve become a millionaire or simply moved away from your hometown, his vibrant lyricism captures what it is like to feel that sense of disconnect once you’ve explored the wider world. It also conveys the guilt you feel for leaving the town that has been left to rot.

These juxtaposing concepts are prominent throughout the album. In ‘Nostalgia’s Lie,’ Fender returns to his hometown to find that it isn’t as wonderful as his memories have led him to believe. Similarly, in ‘Crumbling Empire,’ he acknowledges how lucky he is to be successful, compared to the struggles of his working-class family.

The songs ‘Arm’s Length’ and ‘TV Dinner’ criticise the trappings of fame and celebrity culture. Both of these are designed to keep the audience – whether that’s Fender’s fandom or the media – at a distance to protect his personal space. Once again, this establishes Fender as the observer, creating an insular bubble around himself as a person that nobody can access.

Whilst these themes are conveyed very skilfully in Fender’s lyrics, the music itself lets him down. To produce ‘People Watching,’ Fender recruited Adam Granduciel, the frontman for American rock band The War on Drugs. His music is similar to Fender’s, borrowing a lot of inspiration from heartland rock.

However, where they differ is that Granduciel’s breathy vocals compliment the enormity of his instrumentation, sometimes playing second fiddle to the music itself. Meanwhile, Fender’s most prominent instrument is his voice, central to every song he has ever released.

In order to cultivate a sound that aligns with the observer concept, Fender attempts to utilise Granduciel’s production style. The music is just as loud and prominent as Fender’s vocals, decentring him as the main figure within the album. Unfortunately, he gets swallowed up in the process.

The mixing on this album is incredibly strange sometimes, particularly in the songs ‘Rein Me In’ and ‘Chin Up.’ There are times that the music drowns out Fender so much that I cannot understand a word he is saying. Some people have said that they struggle with understanding his singing due to his accent, but as a Geordie myself, it’s the poor mixing that makes it indecipherable at times.

The most prominent example of strange mixing is in the closing track ‘Remember My Name.’ I liked that Fender chose to abandon his traditional rock sound by experimenting with a brass band, recruiting the local Easington Colliery Band. However, its execution wasn’t the greatest, as it sounds as though Fender is hurling himself over the grandeur of the brass band so that he doesn’t get overpowered. Cynically, I know that this was done to emphasise Fender’s grief over losing his grandparents, but the delivery could’ve been a lot less messy.

The last aspect of the album that positions Fender as the observer is the prominence of his band. Some of them have become notable names within their own right, particularly Johnny Blue Hat, known for wielding his saxophone around St. James’ Park. Although, during this album, with the production becoming bigger, the band’s presence became more noticeable.

In particular, Brooke Bentham, whose harmonies and backing vocals are so prominent throughout the album that she almost becomes the Nicks to Fender’s Buckingham. She adds an extra layer to Fender’s insulation around himself, deflecting the audience from listening to just his voice.

What is interesting to note is that, on release day, Fender’s band showed up at HMV Newcastle to sign copies, not the man himself. As he wades through review after review touting him as the next Springsteen, he’s recruited himself an E Street Band.

‘People Watching’ is not about him; it’s about what he sees. There are no intimate anecdotes from nights out or funerals, just tales from a world that he is disconnected from. I guess that’s what going from the Low Lights Tavern in North Shields to the floodlights in St. James’ Park can do to a man.